This June, more than 50 colleagues and I will be participating in a special conference sponsored by the Faculty of Arts & Sciences, the Center for Public Leadership, and the Graduate School of Business Administration at Harvard University. This conference honors one of my advisors, J. Richard Hackman, a foremost expert researcher in teams. To identify the conditions that encourage effective teamwork, Hackman studied groups including commercial flight crews and the Orpheus chamber orchestra, which does not rely upon conventional leaders but rather collective decision-making by the group. Besides numerous journal articles and co-authoring the seminal book Work Redesign with Greg Oldham, Hackman has also written the book Leading Teams: Setting the Stage for Great Performances, which walks readers through the steps of creating and running successful teams.

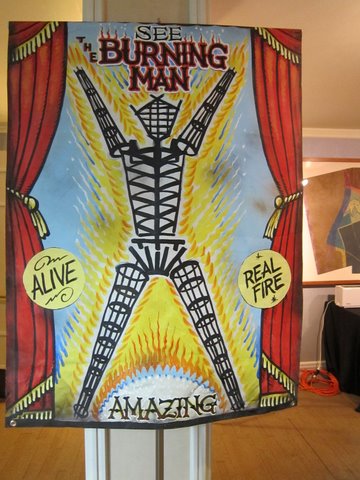

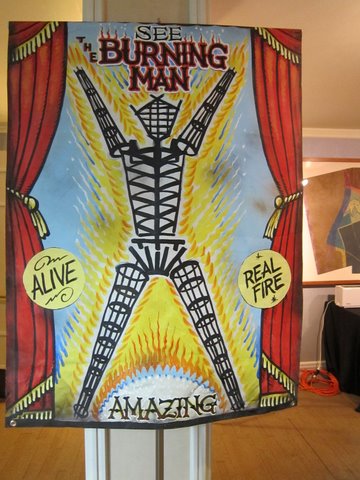

In addition, Hackman has been highly influential in mentoring and teaching organizational researchers such as myself about how to create organizations that are both meaningful and serve members’ interests. In fact, Hackman has been one of the most enthusiastic supporters of my research on Burning Man, which when I first started my field studies, was a mystifying phenomena to most (i.e., at the time, most reactions consisted of “Burning What?!? Is this like the movie Wicker Man?”).

When I initially signed up for this June gathering, I anticipated sipping bubbly over small talk in the hallowed halls of HBS. I soon learned that the conference, dubbed the “Hackfest,” involves working in teams to troubleshoot challenges to teamwork. One issue that we’ll discuss involves “Dealing in real time with “bad actors,” team members who are slowing team progress or undermining the team.” Those of us who manage/work/volunteer in groups inevitably encounter this dilemma. Since most of us are not trained or coached on how to work effectively in groups, we often deal with this challenge through trial and error, with a heavy emphasis on error.

We may not recognize instances in which participants may have different goals or processes in mind and label these persons or their activities as bad rather than understanding their underlying motivations – “undermining” might be one participant’s way of checking groupthink or pursuing an end other than efficiency. For example, some people complain when meetings get derailed by small talk or discussions that don’t lead to tangible outcomes. What we often don’t realize is that meetings aren’t just tools for getting things done; they also serve as social occasions where the collective comes together. On the other hand, we do occasionally encounter individuals who are having a bad day or have a chip on their shoulder; their participation can derail or impede group processes despite our best efforts.

Interestingly, back in May, Burning Man regional leaders at the 5th Annual Burning Man Leadership Summit discussed a similar issue, “How do we deal with divisive personalities while still supporting radical inclusion?”* This and other issues provoked feverish but enthusiastic brain-storming, much of which drew on an earlier workshop on conflict resolution skills. I’ll be paying especially close attention to the “bad actors” discussion at the Hackfest to see whether what the experts suggest lines up with what Burning Man practitioners have proposed. (BTW, in his book Leading Teams, Hackman also recognizes the value of including even seemingly “difficult” individuals.)

*Note that the summit’s wording uses the word personalities, which connotes that this behavior is inherent to a person, rather than the conference’s word actors, which emphasizes activities. Organizational researchers like myself prefer not to use terms like personalities, as we focus on how activities emerge from interactions or situations. For example, all of us have occasionally acted as a “wrench in the machine” by questioning the status quo, but most of us would not characterize ourselves as being inherently divisive.