This past weekend, I joined over 50 other researchers and practitioners at a conference held at the Harvard Business School in J. Richard Hackman‘s honor. To celebrate several decades’ worth of research on group and teamwork, we divided into groups to collectively discuss and identify directions for future research in particular areas. We then presented our findings or recommendations to the larger group.

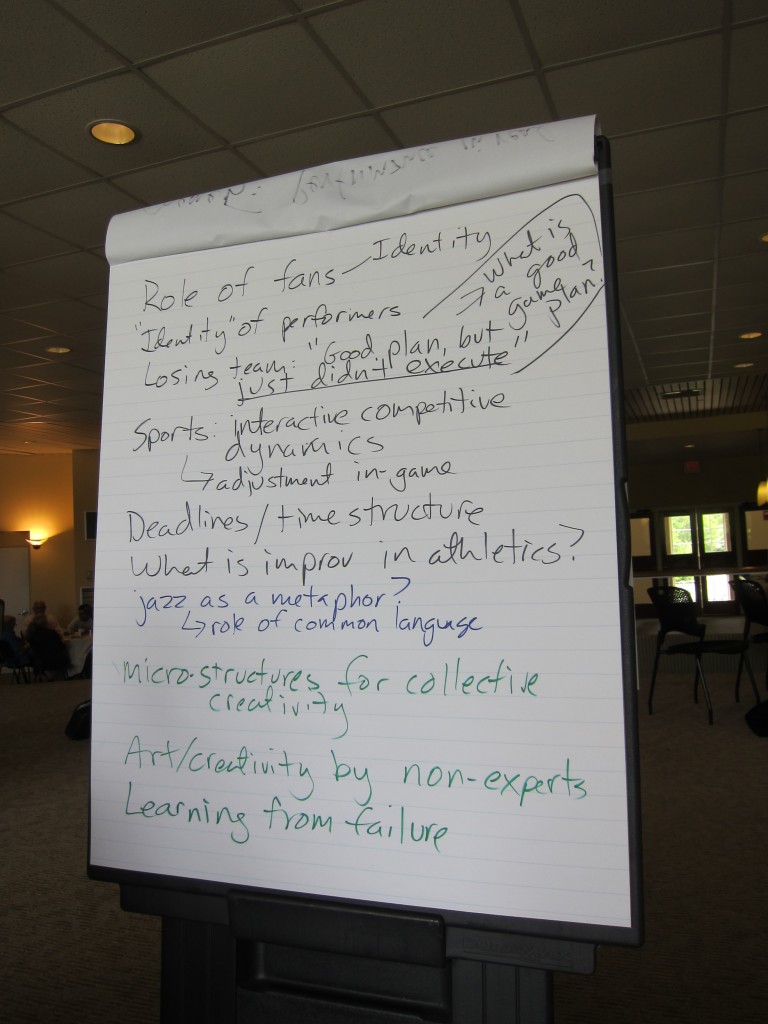

Here’s a sample of our preparations for our topic on “Performing in real time: What is special (or especially interesting) about artistic performances and athletic competitions, with special attention to the dynamics of real-time improvisation”:

Our claim: we can benefit from understanding a major variation among artistic and athletic groups: level of practice – some might say preparation – leading up to performance – such as a game or concert. Some groups don’t practice together at all, like improvised jazz or pick up basketball; others practice in moderation, like community orchestras or athletic groups; a few practice intensively, like professional athletic teams and orchestras. This variation in level of practice can help us also understand other groups that practice/prepare for conventional or unusual situations, such as disaster preparedness.

To illustrate our points, we co-presented the material while accompanied by improvised jazz by Daniel Wilson on the drums and Colin Fisher on the trumpet.

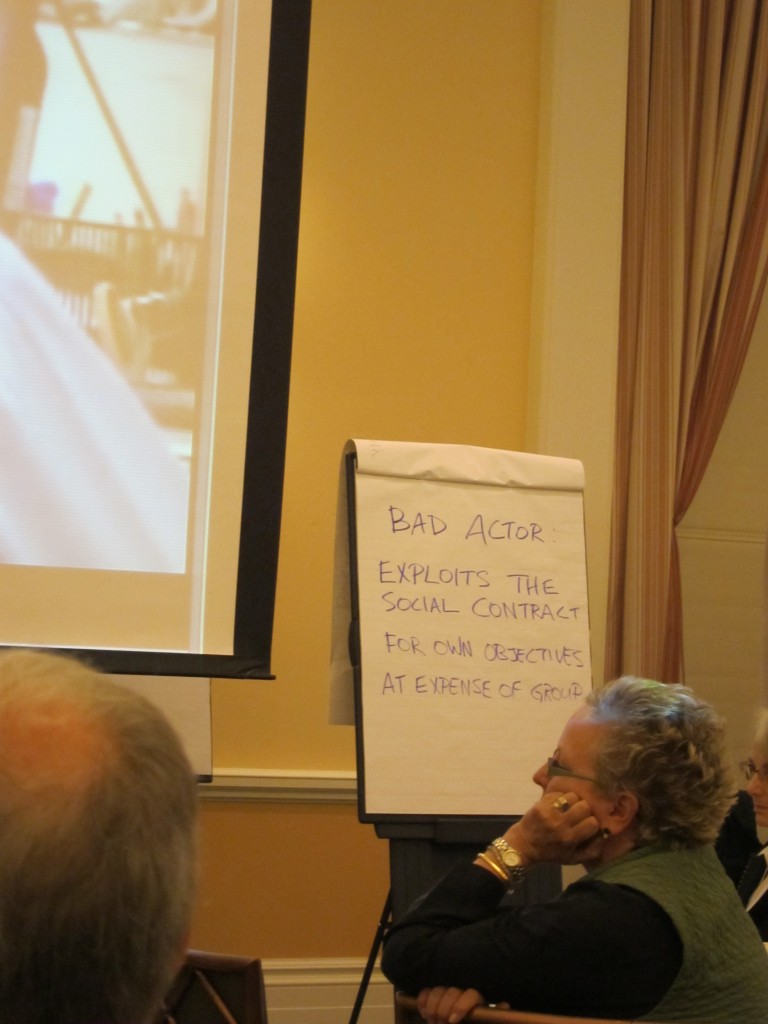

Another group discussed the topic “dealing in real time with “bad actors,” team members who are slowing team progress or undermining the team. Here’s their definition of a bad actor:

They used two clips from the tv show The Office to illustrate their points. They then showed a 2 by 2 typology based on an actor’s position in the authority (low vs. high) and amount of power (too little vs. too much) to identify 4 categories of bad behaviors.

Interestingly, unlike the sessions at the 5th annual Burning Man Regional Leadership Summit, the presentation was too short to offer tools for how to deal with actors who engage in these behaviors. I spoke with one of the group members afterwards, and she reported that although some of the group advocated moving the bad actor around to other groups in the hopes of a “better” fit, others worried that this would contaminate other groups with bad behavior. This suggestion of moving a person around to different groups sounds a little like what Burning Man organizers call “repurposing.” However, in the Burning Man organization, repurposing may be more about making sure that volunteers’ interests fit the task/group. For more on this, see chapter 4 “Radical inclusion”: Attracting and Placing Members of my book Enabling Creative Chaos.